THE GALWAY REBELLION

By a Volunteer Officer (Written and published in an American newspaper)

PREFACE

The story of the Rebellion in Galway, written by a man who took an active part in it and whose name, for obvious reasons, is not given. The newspapers and cabled reports at the time of the Rebellion were full of lies and errors. Among them was the great feat of the British cruiser which “saved” Galway from capture by 1,200 Rebels who were marching on the city, by shelling them from the Bay.

There were not quite 500 Rebels all told, at any time in Galway and they were not within five miles of the spot that was shelled. The shelling of the ground was kept up for several days, but nobody was hit and doubtless great reports were sent to the Admiralty of the havoc wrought among the Insurgents. The object of this waste of ammunition was, of course, to strike terror into the people, but it had no such effect.

While the writer has no hard battle to record, his story shows what might have been done but for the countermand of the Easter Sunday parades and the capture of the German shipload of arms. With less than forty rifles the Insurgents were able to hold 600 square miles of Galway for nearly a week and to disperse safely to their homes when nearly surrounded by a force of several thousand British troops well supplied with artillery and machine guns.

THE GALWAY REBELLION

The Rising in the West of Ireland, as in the other parts where the Volunteers rose, did not assume anything like the proportions it would easily have done had the rebellion started, as was originally intended, on Easter Sunday evening.

The capture of the ship Aud off the Kerry coast, with 20,000 rifles, ammunition, explosives, machine guns, and other equipment aboard, on Good Friday, dealt the greatest blow to the success of the Rebellion. Three thousand of these rifles were to have reached the County Galway on Easter Monday, by which time the entire county would have been in the hands of the Rebels. And there was a Galwayman ready to shoulder every one of the 3,000 rifles, as well as the rifles that would have been captured from the police.

Then Eoin MacNeill’s order countermanding the Easter Sunday night’s mobilisation resulted in great numbers of men being disheartened – good and brave men who were prepared to do all, and more, required of them on the Sunday night. Worse than all, through this order of MacNeill’s the “element of surprise,” upon which the plan of campaign depended, and which was a dead certainty on Easter Sunday, was lost. The police – who in Ireland are not civil functionaries, but an armed standing army – never suspected that anything was intended for that night. They went about their duties as usual. That they had no suspicion, received no warning, and were quite unprepared for the Rising on Easter Sunday, speaks volumes for the integrity, discipline, and earnest patriotism of the Volunteers. At least 1,000 men and hundreds of women in County Galway, as well as the men in the other parts of the country, knew the date and the hour from Easter Sunday, and some several days earlier. Yet nothing leaked out!

As to the projected plans, it is obvious that the present time is inopportune to disclose them. Suffice to say that they were carefully prepared months ahead, every detail that would ensure success and coordination being worked out. The element of surprise lacking, these plans could not be put into operation. When the news reached the West that “Dublin was going out,” the police were alive to the situation and were on the alert. Their first act was to abandon nearly all the smaller barracks, and concentrate themselves in the towns of Galway, Athenry, Gort, Loughrea and Ballinasloe.

The spirit manifested by the Volunteers on Easter Sunday was splendid. Every man was in his place ready for action, and the order postponing the Rising only reached several corps as they were on their way to carry out the part assigned to them.

GALWAY MEN TURN OUT

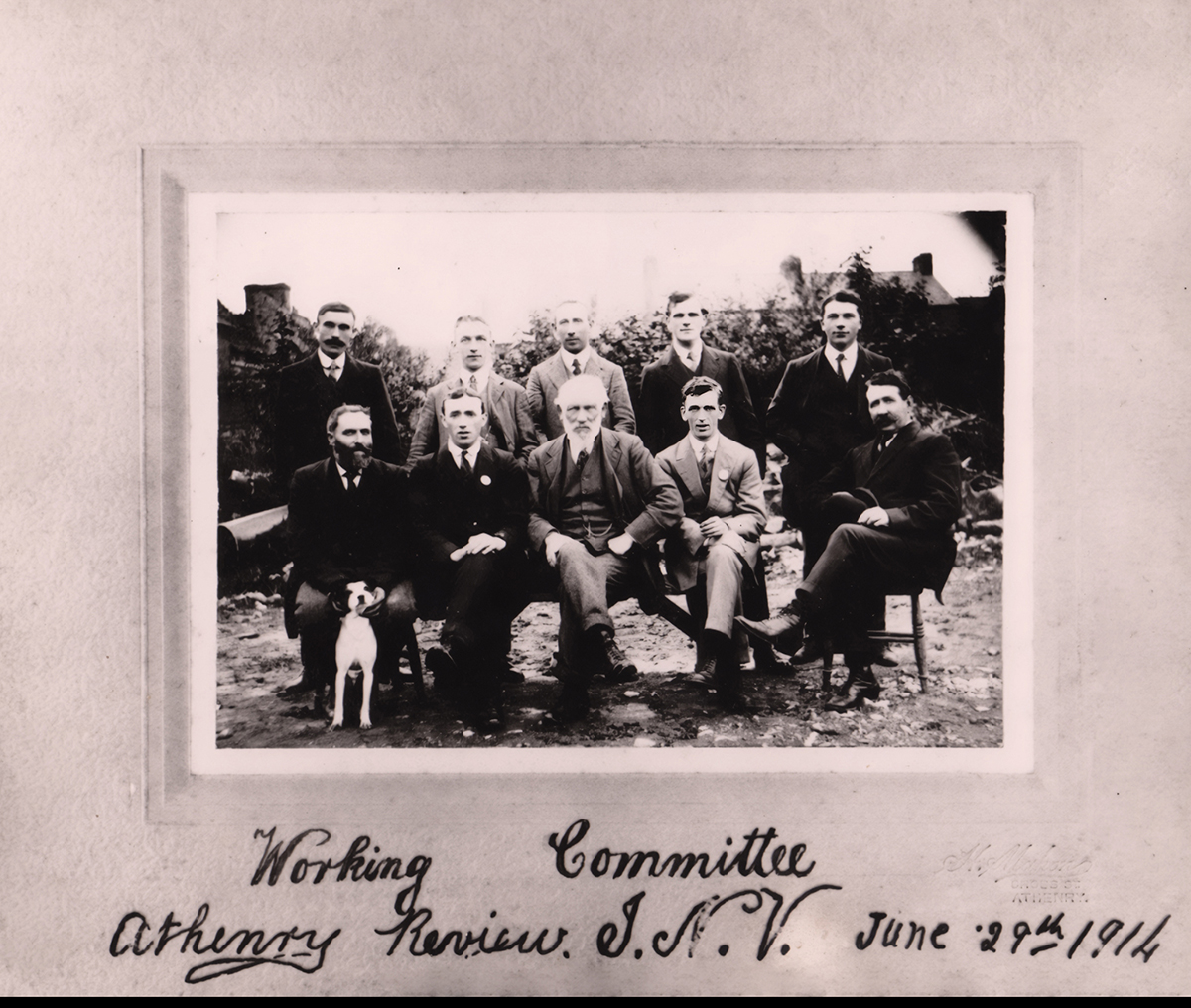

It was known to most of the Galway officers that the British Government had intended for some time previously to suppress the Volunteers. Therefore, when finally the despatch came on Easter Monday that Dublin was out, they decided to go out too, notwithstanding the fact that the men were almost without arms, excepting shotguns. Despatches to this effect were sent to all the corps. Nearly 500 men answered the call. Commandant Liam Mellows was in command. He and Lieutenant Blythe, the two chief organisers of the Volunteers, had been arrested the previous March, and a fortnight before the Rising were forcibly deported to England. Commandant Mellows succeeded in making his escape and arrived back in the West in time for the Rising.

The first act of the Volunteers was to destroy telegraphic and railroad communications. Wires were cut and rails torn up and signal cabins and points wrecked. Roads were also blocked in several places by barricades. On Easter Monday night, Lieutenant Padraic Fahy was sent in an automobile with two men as escort, with an important dispatch. Near Kinvarra, while waiting outside a house, they were surrounded by a large body of police, who held them up with their carbines, Lieutenant Fahy was captured and handcuffed. The driver, jumping aboard his car – the engine of which had been left running – called on the others to follow, and drove away. One of the other two left managed to clamber on behind. The car got away safely, although fired on by the police. The other man who still remained uncaptured drew a revolver, and, after an interchange of shots with the police, escaped safely. Lieutenant Fahy was afterwards taken to Limerick by the police, court-martialled, and sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude.

CLARINBRIDGE BARRACKS ATTACKED

At 7 A. M., Tuesday, the Clarinbridge and Killeeneen Corps occupied the village of Clarinbridge and attacked the police, who acted on the defensive in their barracks. An attempt to rush the place failed, and firing on both sides went on for over an hour. Then several bombs exploded in the barracks. To do this Captain Eamonn Corbett, who volunteered for the job, had to rush up to the windows of the barracks, under fire and throw the bombs inside the barracks. This he did successfully six times.

While this was being done, huge barricades of trees and stones had been thrown up at each end of the village and several police scouts captured. One of these did not surrender quick enough and promptly received the contents of a shotgun in the face. The public houses (saloons) were shut and horses and vehicles commandeered. A couple of motor-cars, and one motor-van were also secured.

THE FIGHT AT ORANMORE

Meantime the little town of Oranmore, three miles north of Clarinbridge, had been occupied by the Volunteers from Oranmore and Maree districts. The barrack here was strongly defended by the police. The Rebels besieged the place and heavy firing was engaged in for several hours. The Midland Great Western Railway, which runs through Oranmore, was destroyed in several places. Several police were captured here. One of them a “plain clothes” man, went out of his mind the next day, probably with fear.

At 4 P. M., the Volunteers from Clarinbridge arrived at Oranmore. They were all mounted on vehicles of some description, none of them having to march on foot. Of the police in the Clarinbridge Barracks, only four came out of it, and these were all badly wounded – evidently by the explosion of the bombs. As in Clarinbridge, the public houses were shut by the Volunteers, and no drink was allowed to be sold at all. The Rev. Father Feeney accompanied the force from Clarinbridge and was through the Rising from start to finish, encouraging and inspiring all by his presence and example.

A plucky attempt to drive the police out of a house they had fortified by a small body of Rebels under Lieutenant Martin Costello, was repulsed by heavy fire, one of our men being badly wounded. Captain Corbett was ordered to take a few men and blow up the bridge at Oranmore on the main road to Galway city. One explosion had taken place and a large hole was made in the bridge when a strong force of police and military sent from Galway to relieve Oranmore arrived on the scene. The Volunteers, who then numbered ninety men, were forced to retire in the direction of Athenry. The retreat was carried out in perfect order, a small group of Rebels engaging and holding back the British while the remainder got away. In the execution of this the police are believed to have lost eleven, and according to another report, thirteen men.

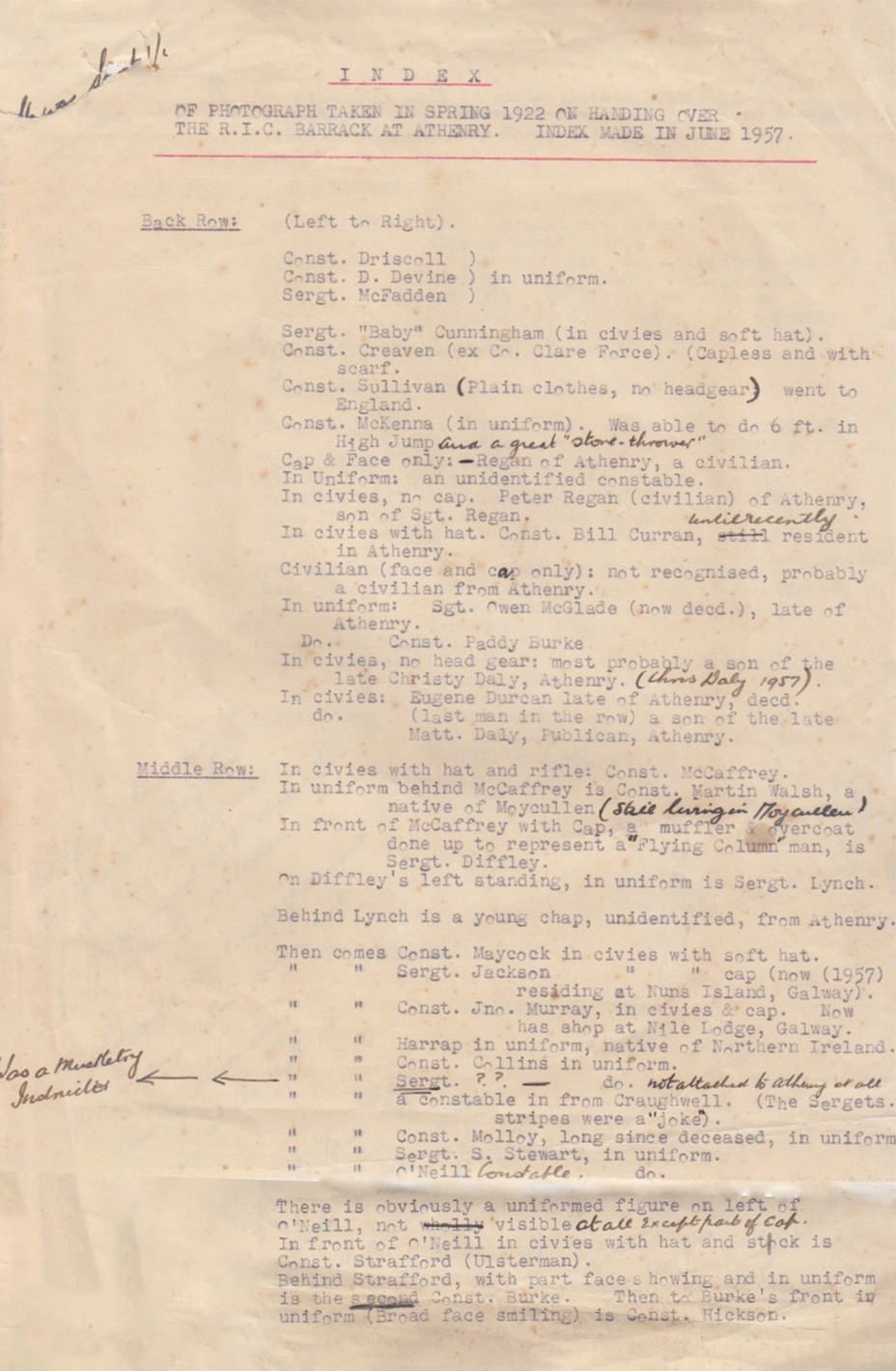

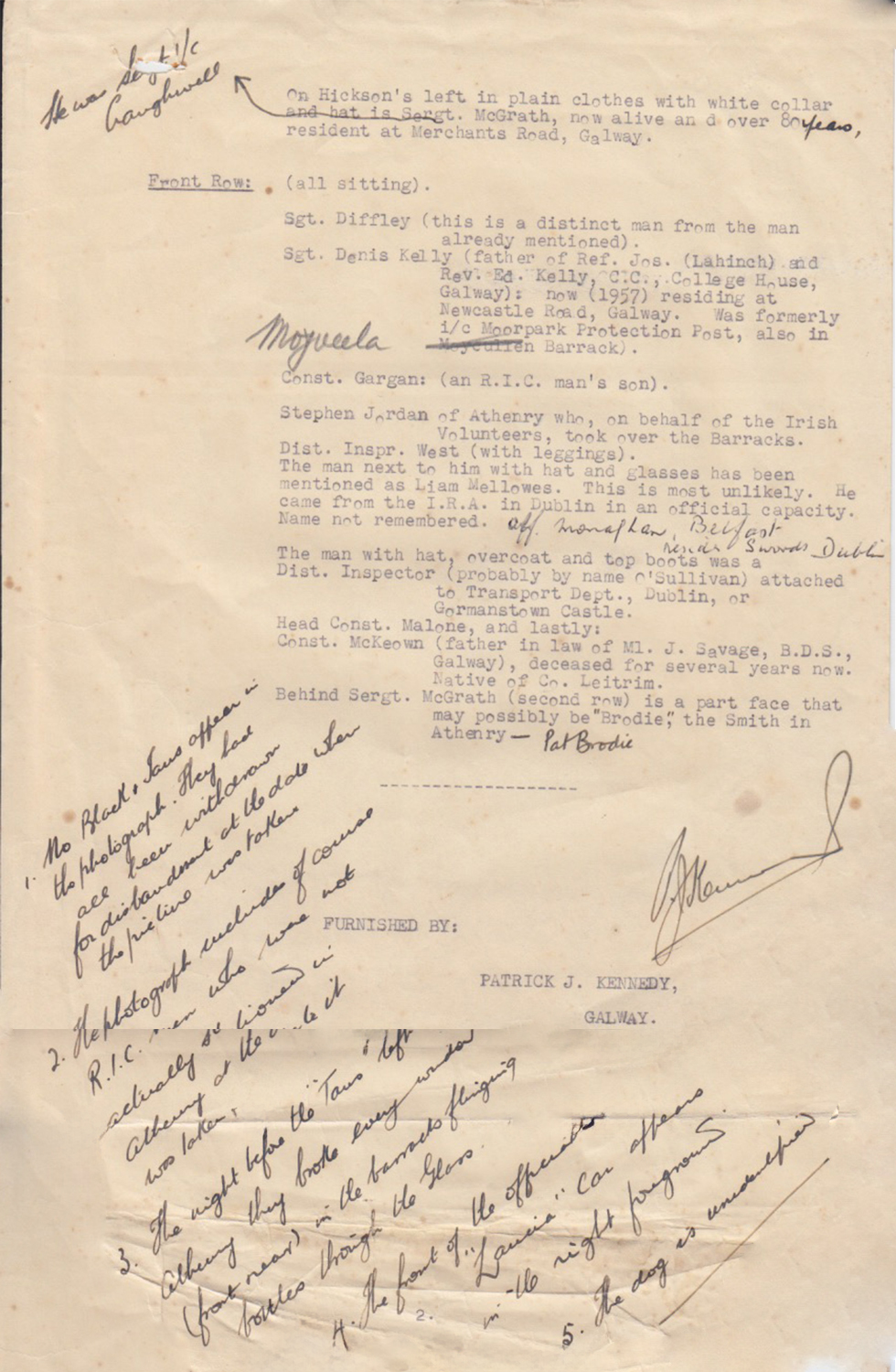

OPERATIONS AT ATHENRY

The next move made by the Volunteers was in the direction of Athenry, seven miles east of Oranmore. When one mile from the town, they were met by the Athenry Volunteers, who were forced to evacuate the town, which was now strongly held by 200 well-armed police. It was now 9 o’clock at night. The Volunteers bivouacked at the Model Farm of the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction for Ireland. Here they stayed for the night, ample accommodation being found in the big lofts. Their numbers had now increased to almost 500 men, but there were very few rifles – forty at the outside. For the greater part they were armed with shotguns while a few had no arms at all. These latter were put driving carts and taking care of the horses. At the Model Farm butter, milk, cattle, corn, flour, horses, carts, tools and implements were commandeered.

The next morning, Wednesday, at 7 o’clock, a reconnaissance in force by the police from Athenry, was driven back by our outposts, the police retiring hurriedly into the town, with two of their number wounded. None of our men were hit.

VICTORY AT CARNMORE CROSSROADS

Earlier in the morning a force of military from Galway, with a few police as guides, were hurried in motors in the direction of Athenry. They were commanded by Captain Bodkin and District Inspector Heard, Royal Irish Constabulary. At Carnmore Crossroads, six miles from Galway, they were ambushed by fourteen men of the Carnmore and Claregalway Corps. These men were waiting for the remainder of the Corps to turn up, with the intention of joining the main body of Volunteers at the Model Farm, when the enemy appeared. The military opened fire at once and one of the Peelers, jumping on a wall and calling on the Rebels to surrender, was shot dead. The enemy retreated headlong, followed by a volley from the shotguns of the little group of Rebels. Heard, the District Inspector, and several police and soldiers were wounded in the retreat and only the speed of their cars saved the whole force from being cut off by the Volunteers. The British report of this affair is that our men retreated hurriedly across the fields, several of them being killed. This is an utter lie and was probably fabricated by the gallant Captain Bodkin or the more gallant District Inspector to save their military reputation.

WARSHIPS BLOW HOLES IN THE GROUND

On this day, Wednesday, British warships arrived in Galway Bay and shelled the shore west of Galway city and also in the direction of Oranmore. No damage, however, was done to the Rebels, beyond the holes ploughed in the earth, though the British fondly imagined they had dislodged the Rebels, whom their report stated as having fled in confusion. This was not so, for the very simple reason that the Rebels were not within five miles of where the shells landed.

Marines and sailors, with machine guns, were landed off the warships, and Galway city prepared by the British for a siege. The police in Galway had arrested Messrs. George Nicholls, B.A., solicitor, Dr. Walsh, and other prominent Nationalists and Volunteers in the city earlier in the week. These were put on a mine-sweeper and conveyed at once to England.

On Wednesday afternoon the Rebels marched to Moyode Wood, four miles east of Athenry, because it offered better facilities for defensive warfare than the Model Farm. In the wood was a castle-residence, belonging to Lord Ardilaun. Here the men were billeted. Cattle were commandeered and slaughtered and everything possible done to make the men as comfortable as possible.

REORGANISING THE REBEL FORCE

Owing to the dislocation of plans and the disorganisation consequent upon the countermanding and postponement of the Rising, it became necessary to reorganise our force entirely. This was effected when all the men were concentrated at the Model Farm. New officers and section leaders had to be appointed in cases where the original commanders had not turned up. Commissariat and transport departments had to be organised.

The former was put in charge of Lieutenant Jack Broderick, of Athenry. He took up his duties with a zeal and enthusiasm wonderful to behold. In a short while he had a staff of several butchers and other helpers. He organised commandeering parties and dispatched them for anything he considered necessary. Cattle were slaughtered, but no more than were absolutely needed. The girls of the Cumann na mBan were set on baking bread and rations were issued to the men. Each company appointed orderlies and cooks to draw rations and prepare meals. One of the cooks developed a genius for making stew and the quarters of the Athenry corps, to which he belonged, was generally invaded about meal times by men from all the other corps, attracted there by the savoury smell. Officers, going about their duties were hailed on all sides by amateur cooks, with cries of “Ate a bit o’ this, Captain, ‘tis grand,” “Try a little of the Castlegar mate.” Throughout the week the Commissariat Staff worked splendidly and everything was done to feed the men.

The Transport Department was put in the hands of Lieutenant Matt Neiland. Before long he had horses and carts of every description ready – farm-carts, traps, vans. A water cart was discovered at the Model Farm and it was also used. Drivers were appointed. Each driver’s sole duty was to feed and look after his horse, to know what load he would have on his cart, and where it was to be found. The Transport Department and the Commissariat worked hand in glove. Test mobilizations were practised and it was found, when things got working smoothly, that in five minutes from the time the mobilisation whistle went the whole force was ready to march, with baggage and stores loaded, horses harnessed, drivers ready.

SUPERB SCOUTING BY THE REBELS

The scouting of the Rebels was particularly good. Nothing passed unknown to them. Everywhere the people received our men with pride, while information of every kind was brought hourly by women and girls of events happening in their different localities. Some of the best scouting was done by boys. One young lad of fifteen particularly distinguished himself in this respect. All the scouts were first-class cyclists, and had nearly all been trained by Lieutenant Pat. Callanan of Killeeneen, who performed great work in this line himself, undertaking many arduous, trying and dangerous journeys to acquire information and bring despatches. He accomplished everything successfully and his report was always to be depended on.

A special edition of the Connacht Tribune, one of the worst of all the denationalised rags that have prostituted Irish Nationality since the war, appeared this day. It described the Rebellion in Ireland as “the most formidable since ’98.” And, remarkable to relate, this paper, that week after week had calumniated the Volunteers and their officers in Galway, had nothing bad to say against the “Rebels.”

On Thursday, a couple of skirmishes occurred with the enemy. In Kinvarra the local corps attacked the barracks without result, however. A patrol of our men had a sharp conflict with a patrol of the enemy close to Athenry. The police retired, and a flying column of Rebel motor-cars from Moyode Wood hotly pursued them, the police fleeing back to the town as hard as they could run. That night a battery of artillery moved from Ballinasloe in the direction of Athenry, but returned after proceeding a few miles. Evidently they feared being ambushed by the Rebels.

REBELS HELD 600 SQUARE MILES

During this week all Central and South Galway was free territory, with the exception of the town of Athenry. That is to say, from close to Galway City east to Ballinasloe and from Tuam south to Gort – about 600 square miles. Everywhere the people showed the greatest kindness to the Volunteers; gave them their blessing and wished them success. The greatest enthusiasm prevailed amongst the Rebels. About thirty girls, members of the Cumann na mBan, accompanied their brothers-in-arms the whole week. Their spirit and determination was wonderful. Nothing could damp the spirits of all who were “out.” Songs and recitations were to be heard on all sides when resting. Laughter and fun never deserted them. The police, in abandoning several of their barracks and huts, were in such a hurry that they left uniforms, clothing and boxes and kits behind them. Several of the irresponsible mirthmakers amongst the Volunteers, dressed in Peelers’ uniforms and strutted about imitating the authoritative airs of the sergeants – the little Czars of their district.

Several priests visited the Volunteers this day, Thursday. Confessions were heard all day.

The warships continued bombarding the shore near Galway city all this and the following days, till long after the Rising was over.

THE ARMY CLOSES IN

Ballinasloe by this time was crammed with soldiers – horse, foot, and artillery. Police were being rushed into Galway by the hundred from the North of Ireland. Yet it was not till the following evening (Friday) that they moved near the Rebels. On Friday morning a scouting party of Rebels penetrated east to within six miles of Ballinasloe. The police barracks at New Inn was raided by them, and the sergeant taken prisoner. Amongst other documents found in the barracks was an order from the local District Inspector, dated early that morning, telling the police to evacuate the barracks. The sergeant, however, was not to go, but was to remain behind to identify anyone who came to the place. In order to do this he was to remain in bed and plead illness if the place was occupied by the Rebels – the Inspector’s order naively remarking that the Rebels would not touch him if he were ill.

On Friday evening the military and police were to move on Moyode. The orders they had were to “take no prisoners.” However, before they could put this “war for civilization and small nationalities'' order into practice, the Volunteers moved south in the direction of Clare. The reason for their doing so was because it was believed that Cork and Kerry were out and that a junction would be affected with them, rousing Clare on the way. Notwithstanding the fact that they were practically hemmed in at the time, the little band of Rebels managed to march nearly eighteen miles southwards – almost to the borders of Clare. Here a halt was called.

It was now early on Saturday morning. The news that had trickled through from Dublin during the week up to this, was of the most heartening and inspiring kind. The city was in the hands of the Rebels everywhere. The British had been repulsed time and again with great losses and a desperate conflict was raging. Now the news was of a different character. Dublin was in flames and a surrender was contemplated – and Cork and Kerry were not out.

REBELS DECIDE TO DISBAND

A meeting of the officers was held. After a discussion of affairs, it was decided to disband. Without proper arms, with Dublin surrendering and the South of Ireland not fighting, it was felt by most of the officers that it would be pure slaughter of the men to keep on. A couple of the officers fought vigorously against the disbandment, protesting that it would be better to fight it out to the bitter end, as Conscription would surely be enforced at once. Nevertheless they were outvoted and the disbandment took place. That the British Government did not enforce Conscription, as was their intention previous to Easter, was entirely due to the Rising – to the terrific fight put up by the Dublin Rebels against the forces of oppression whereby the lie was given to England’s oft reiterated statement that Ireland was loyal to the Empire, and whereby it was demonstrated to the world that England’s plea that her entry into the Great War was on the behalf of small nationalities, was hypocrisy and a sham.

BRITISH BRUTALITIES AFTER THE RISING

The vindictiveness of the British Government after the Rebellion in Ireland, in which Irishmen fought for their own small nation and civilization, was appalling. The police in the West particularly excelled themselves. Hundreds were arrested, whole villages being cleared of men and boys, the prisoners being treated in the most brutal fashion. Several women were also arrested. Houses were wrecked in the most wanton fashion, the same place being visited time and again, and all it contained destroyed. Women and girls were threatened with loaded rifles and fixed bayonets levelled at their breasts, in order to extract information regarding their husbands and relatives. Need it be said none of these threats had any effect.

Of those who took part in the Rising in Galway, Captain Bryan Molloy was sentenced to death, but it was commuted to ten years’ penal servitude; Lieutenant P. Fahy to ten years’ penal servitude, thirty-eight to three years’ penal servitude; twelve to twelve months’ hard labour, and hundreds of others were deported to England.

The hunt for a few of the principal officers was carried out with fearful intensity. The order issued by the military authorities concerning them was that they were to be shot on sight, but they were never shot.

POLICE DESECRATE A CONVENT

About a week after the Rising the Convent of the Presentation Nuns at Kinvarra was searched by the police and military on the pretext that Father Feeney and Commandant Mellows were hidden there. The Convent was first surrounded, and then the Reverend Mother was questioned. She declared on her word of honour that no one was concealed in the convent, but her word of honour was not good enough for the “gentleman” who commanded the gallant forces of the Empire. The convent was ransacked, and the nuns’ cells burst into and searched; and, of course, nothing was discovered.

The gagged and subsidised Irish press had not one word to say about this outrage, though the horrors and atrocities of Belgium, Servia, Montenegro, and other places of more Irish interest than Kinvarra, were painted with a heavy and loving hand.

A month after the Rising was over, the British soldiers quartered in Athenry were going about with medals, rosary beads and other articles of religious interest. They were in fear of another outburst and thought these might protect them. And they were Protestant to a man.

Since the Rising the spirit of Connacht is better than ever it was. The ambition of all is expressed in the hope that they will be in at the “final.”

|